I

n his article, The Surrounded: #NoDAPL and Geographies of Indigenous Resistance, Nick Estes (2016) explains that “the Native is usually cast as surrounded by the settler, bounded within highly restrictive and ever-diminishing territories that are under constant surveillance and assault” (12). A contemporary example of this is the ongoing siege against water protectors and their allies at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, in Cannon Ball, North Dakota. Any investigation into the historical and political context of the #NoDAPL movement will reveal an extensive history of Oceti Sakowin (The Great Sioux Nation) resistance against “the trespass of settlers, dams, and pipelines across the Mni Sose, [or] Missouri River” (Estes, 2016, Sept 18). Since 1803—when the fledgling U.S. settler state first “claimed” Oceti Sakowin territories[1]—the Sioux have struggled against ongoing state violence, as well as an onslaught of imperialistic maneuvers aimed at acquiring Indigenous lands and waterways, and extracting natural resources (Estes, 2016, Sept. 18). Despite strong protest, over the past two centuries, millions of acres of Oceti Sakowin territories have been lost to the encroachment of the white settler state.

Our art forms are never separate from our political forms.– Wanda Nanibush, 2014

In what can only be regarded as the most recent form of settler colonial expansion in the region, the US government has approved construction of a 1,886 km (1,172 mile) Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL)—which, when completed, will transport nearly half a million barrels of highly volatile crude oil across a large portion of the northern United States, each day (Estes, 2016). Projected to run from the Bakken oil fields in western North Dakota to southern Illinois, the pipeline will cross beneath both the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, as well as under part of Lake Oahe near the Hunkpapa Oyate (Standing Rock Sioux Reservation). As the pipeline represents a huge threat to the regions access to clean air and water, in early 2016 a large grassroots movement was formed at the Oceti Sakowin Camp, the largest of several camps (including Red Warrior Camp and Sacred Stone Camp) situated north of the Missouri River; “more than three hundred Native nations and allied movements have planted their flags in solidarity at [Standing Rock]” (Dhillon & Estes, 2016). In direct opposition to pipeline construction, in particular, and the fossil fuel industry more generally, the #NoDAPL movement follows in the long tradition of Sioux anticolonial resistance; e.g. while the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851—which first established the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation—binds the United States government “to protect [Indigenous] nations against the commission of all depredations by the people of the United States” (Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, 1904), treaty provisions have been repeatedly violated. Thus, #NoDAPL can be understood, in many ways, as a continuation of nineteenth-century struggles for Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty, as well as for the continued protection of Oceti Sakowin homelands (Dhillon & Estes, 2016); “The scope of the resistance at Standing Rock exceeds just about every protest in Native American history. But that history itself, of Indigenous people fighting to protect not just their land, but the land, is centuries old” (Donnella, 2016, Nov. 22).

Artists, we live on the periphery. But we are the mirrors.– Cannupa Hanska Luger, 2017

For Estes (2016), to be Indigenous is to exist in a perpetual state of “fugitivity” (12); “[Indigenous peoples] are imagined as always on the lam from progress and civilization, as much as they are thought to have disappeared or [to] be in a constant state of disappearing” (Estes, 2016: 12). In other words, Estes’ (2016) conception of the fugitive suggests that Indigenous peoples have been repeatedly characterized by settlers as existing “outside” of history, as being “inherently criminal” and in need of constant state surveillance. And while this particular understanding of fugitivity is extremely useful when describing the precarity of life under settler colonial occupation for Indigenous peoples, I would like to propose that an alternative conception of the fugitive is necessary when discussing the creative forms of resistance that have defined much of the #NoDAPL movement. What follows is a meditation on the idea of Indigenous fugitivity as radical glitch, or “glitchfrastructure” (Berlant, 2016).

According to Lauren Berlant (2016) “[a glitch] is an interruption within a transition, a troubled transmission. [It is] also the revelation of an infrastructural failure” (393). Interestingly, Berlant (2016) makes the argument that the “glitch of the present” works to reveal “what, [up until that point,] had been the lived ordinary, the common infrastructure” (403)—“When things stop converging they […] threaten the conditions and the sense of belonging, but more than that, of assembling” (403). I suggest that the concept of the glitch is similar to, or rather, complementary to, that of Indigenous fugitivity. That the two often work together. Indeed, an act of fugitivity may result in a glitch, and, conversely, a glitch may enable acts of fugitivity. For Jarrett Martineau and Eric Ritskes (2014) “Indigenous art is inherently political” (I). A site of both resistance and (re)surgence, as well as a manifestation of creative praxis, Indigenous art has the potential to (re)inscribe Indigeneity within aesthetic forms (Martineau & Ritskes, 2014). Drawing on the work of Gerald Vizenor and Walter Mignolo, Martineau and Ritskes (2014) define fugitive spaces of Indigeneity as “the critical ruptures where normative, colonial categories and binaries break down and are broken open” (III) Importantly, it is from within these breakages and fissures that (de)colonial artwork emerges (Martineau & Ritskes, 2014). But how might Indigenous creative practices also function as radical glitch? And, in the context of the #NoDAPL protests, how might we conceive of the connections between art, activism, resistance, and resurgence as a form of Indigenous fugitivity? In an effort to answer these questions, I turn to the work of Indigenous artist Cannupa Hanska Luger.[2]

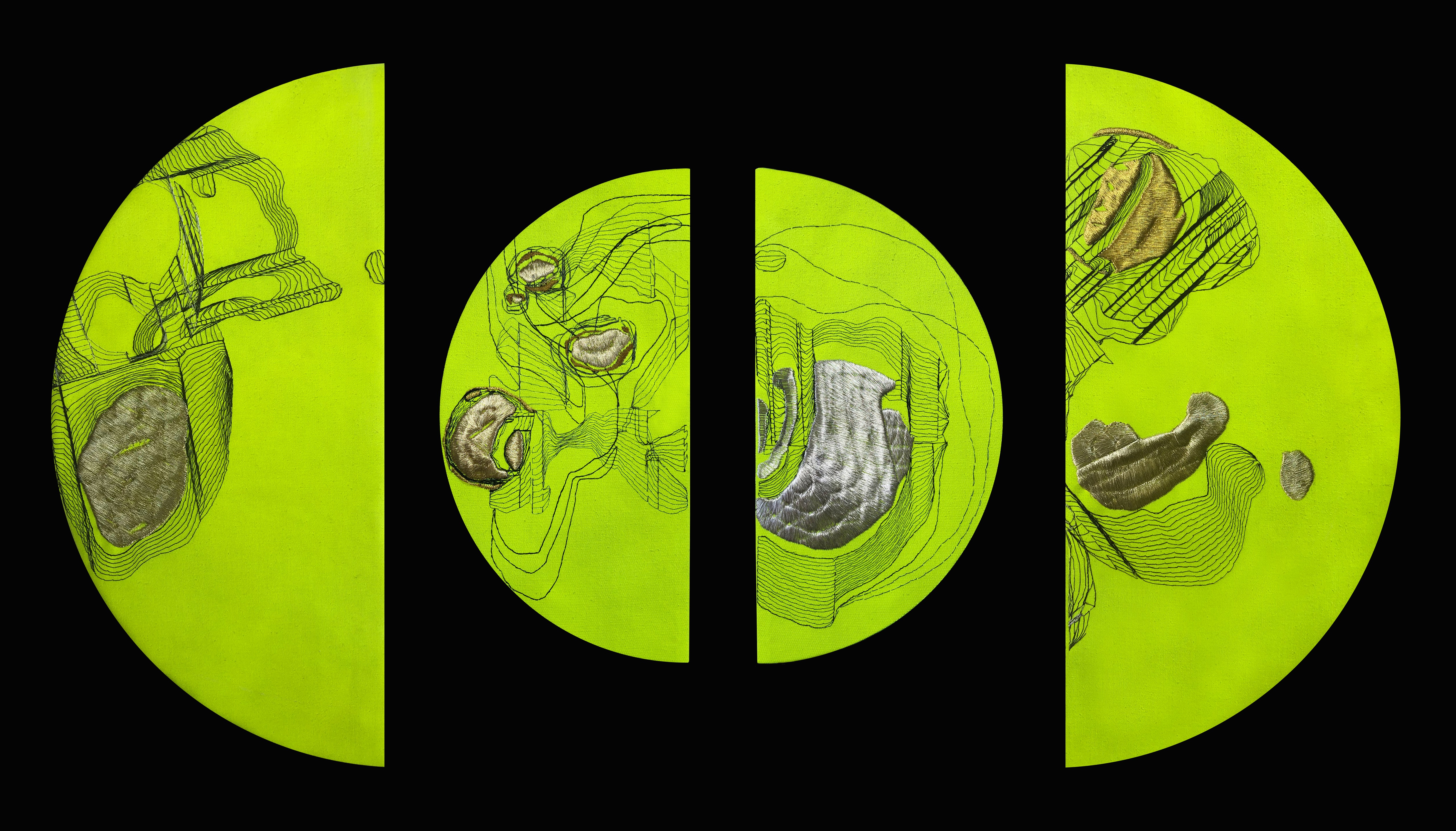

An active supporter of the #NoDAPL protests, Luger made international headlines when he crafted and distributed several hundred mirrored shields to water protectors situated along the front lines (see fig. 1); “I was inspired by these activists in the Ukraine. These women—old women and children—they came out and carried mirrors from their bathrooms into the street to show these riot policemen what they looked like” (Luger as quoted in Miranda, Jan 12, 2017). After witnessing people being forcibly struck with water hoses, Luger decided to manufacture mirrored shields from vinyl and Masonite (materials you can find in any local hardware store); “I didn’t want people to bring mirrors to the front line and get hit with batons and cause more damage than good. So what we needed was a mirrored shield” (Luger as quoted in Miranda, Jan 12, 2017). Straddling the line between art installation and practical defense equipment, Luger’s shields can be read as a powerful (re)appropriation of the riot gear worn by state police and private security firms (see fig. 2). I suggest that they can also be interpreted as a “reinvention of infrastructure” (Berlant, 2016), in this case the tools of settler colonialism, and, as such, that they might function as a radical form of “glitchfrastructure” (Berlant, 2016).

If we can understand the creation and distribution of riot gear—masks, helmets, batons, bullet proof vests, shields, etc.—during moments of civil unrest as “the common infrastructure” of settler colonial occupation, how might the (re)imagining of riot gear by water protectors be read as a “revelation of infrastructural breakdown”? Furthermore, how might Luger’s mirrored shields function as glitch, interruption, and/or hiccup? For Berlant (2016),

institutions enclose and congeal power and interest and represent their legitimacy in the way they represent something reliable in the social, a predictability on which the social relies. Institutions norm reciprocity. What constitutes infrastructure in contrast are patterns, habits, norms, and scenes of assemblage and use (emphasis mine; 403).

By rupturing the predictability of the settler colonial response to mass civil unrest, via the (re)purposing of the very tools that were being used against them by riot police, Luger is revealing a breakdown in both institution and infrastructure.

As instruments of protection and reflection, the mirrored shields serve both a practical and aesthetic function; not only do they deflect the impact of water cannons and withstand the force of police batons, they create an unanticipated, and highly effective, physical barrier between the colonial police and the water protectors. In this sense, the mirrored shields—as radical glitch—serve to rupture the framework of settler colonialism, thereby providing fugitive glimpses (or openings) into (de)colonial possibilities. Additionally, by reflecting power back to power (byway of the mirrored shield) Luger is not only forcing the riot police to confront their complicity in ongoing settler colonial violences, he is subverting the colonial gaze itself (as the colonizer frequently engages in the panoptic[3] maneuver of seeing all while remaining entirely unseen). This reversal of colonial power dynamics is extremely important to note, as Luger is essentially (re)working the terms of reciprocity through the creation of alternate “patterns, habits, norms and scenes of assemblage and use” (Berlant, 2016: 403).

For all of these reasons, I cannot help but read Luger’s artwork as a powerful form of Indigenous fugitivity and radical glitchfrastructure. To quote Martineau and Ritskes (2014), “Indigenous art reminds, remembers, and calls out to us to account for colonial injustice, [it helps us to] realize the potential freedom found in our creative transformation of the world” (V). Ultimately, I posit that fugitive aesthetics represent a particular space through which Indigenous peoples and their allies might continue to (re)claim/(re)map[4] the terrain of (de)colonial struggle—might continue to glitch portals into “worlds otherwise” (Escobar, 2007).

Notes

[1] In 1803, 827 million acres were “bought” from the French Crown in the Louisiana Purchase by the United States government; two white explorers, Lewis and Clark, were sent to “claim and map the newly acquired territory” (Estes, 2016, Sept. 18). Importantly, “none of the Native Nations west of the Mississippi consented to the sale of their lands to a sovereign they neither recognized nor viewed as superior” (Estes, 2016, Sept. 18).[2] Born and raised on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, Luger is of Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, Austrian, and Norwegian descent. Using his art as catalyst, Luger “invites the public to challenge expectations and misinterpretations imposed upon Indigenous peoples by historical and colonial social structures” (Luger, 2017).[3] The panopticon is a type of institutional building designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham. In the late 18th century the design was extended to prison infrastructure, as it would allow for all inmates to be observed by a single watchmen who would remain entirely unseen. The concept of panopticism was first developed by French philosopher and social theorist Michel Foucault in his work Discipline and Punish, and refers to the way in which biopower operates within a disciplinary society.[4] I was first introduced to the concept of “(re)mapping” by Mishuana Goeman (2013); who, in her book Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations, provides a nuanced and significant analysis of the various ways in which Indigenous peoples are (re)mapping the terrain of settler colonialism to include their histories/stories/experiences. I would also like to acknowledge how influential the collaborative work by Jarret Martineau and Eric Ritskes (2014) has been to my research on (de)colonial aesthetics.

.jpeg)